We are professional China Custom Vinyl Fence Manufacturers with fences virgin PVC/Vinyl material and UV Protected.

For generations, livestock management was dictated by permanent fencing. While sturdy and reliable, barbed wire and woven wire create a static landscape, confining animals to the same pastures and leading to overgrazing, soil compaction, and inefficient forage use. Today, a quiet revolution is underway, led by a simple yet transformative tool: the portable electric fence.

This isn’t just about containing animals; it’s about managing an ecosystem. Portable electric fencing is the physical manifestation of managed intensive grazing systems like rotational grazing, paddock shifting, and strip grazing. It empowers farmers and homesteaders to work with the land, not against it. If you’re still looking at that spool of polywire as just a temporary barrier, you’re missing its true potential as the most powerful management tool in your arsenal.

This article will move beyond the basics to provide a deep, practical understanding of how to select, set up, and succeed with portable electric fences for temporary grazing.

The Unbeatable Advantages: Why Go Portable?

The benefits of portable electric fencing extend far beyond simple mobility. When implemented correctly, it creates a cascade of positive effects for your land, your animals, and your bottom line.

Maximized Forage Utilization and Pasture Health: This is the core benefit. By moving animals frequently, you prevent them from grazing their favorite plants to the ground. They take a single, uniform bite and are moved on, allowing the forage a crucial recovery period. This practice:

Encourages Deep Root Systems: Healthy, unstressed plants develop robust roots, which improve soil structure and water infiltration.

Increases Plant Diversity: Weeds are often opportunists that thrive in overgrazed or stressed pastures. Dense, healthy forage out-competes them naturally.

Boosts Carrying Capacity: Many users find they can support more animals on the same acreage by simply managing grass growth more efficiently.

Dramatic Cost Savings on Feed: The single largest expense for most livestock operations is feed. By extending the grazing season—both in spring and fall—and ensuring animals are always eating the best available forage, you can drastically reduce your hay and grain bill. A well-managed system can often provide fresh forage for weeks longer than a continuously grazed pasture.

Manure Management and Soil Fertility: Instead of manure being concentrated in loafing areas and sacrifice lots, it is evenly distributed across your entire property. This acts as a free, slow-release fertilizer, constantly cycling nutrients back into the soil. You are, in effect, using your livestock to fertilize your fields as they graze.

Unmatched Flexibility and Adaptability: Need to graze a back field that has no permanent fence? No problem. Want to create a small paddock in your garden for a few sheep to weed? Easy. Need to protect a newly seeded area? A portable fence is your answer. This flexibility allows you to respond to changing conditions, weather, and forage availability in real-time.

Building Your System: A Guide to Components

A portable electric fence system is more than just a wire. It’s an interconnected circuit. Understanding each component’s role is key to building a reliable one.

1. The Energizer: The Heart of the System

Never call it just a “fencer.” The energizer is the pulse generator. Its job is to take power from a source and convert it into short, high-voltage, low-amperage pulses. Choosing the right one is critical.

Power Source: Solar is the gold standard for true portability in remote fields. Battery-powered units offer a good balance, while plug-in models are most powerful for semi-permanent setups.

Output Joules: This is the power rating. A basic rule: Buy twice the power you think you need. A .5-joule unit might be fine for a small paddock with well-trained sheep, but a 3-6 joule energizer is a better investment for larger areas, longer fences, or more challenging conditions (like dry, weedy soil). It provides a “reserve” of power to overcome minor faults.

2. The Conductor: What Carries the Charge

This is your “wire.” The choice depends on your livestock and duration.

Polytape (½" to 1.5"): Highly visible and psychologically effective, especially for horses and flighty animals. It’s durable for semi-permanent setups but bulkier to roll and unroll.

Polywire (6-9+ strands): The workhorse of portable fencing. It’s a blend of stainless-steel filaments woven into polyethylene string. More strands mean more conductivity. It’s lightweight, easy to handle, and ideal for daily moves.

Polyrope (¼" or more): Thicker and stronger than polywire, it’s excellent for larger animals like cattle that might test the fence. It’s very durable and highly visible.

Braided Polywire: A premium option with superior conductivity, allowing for much longer fence runs with less voltage drop.

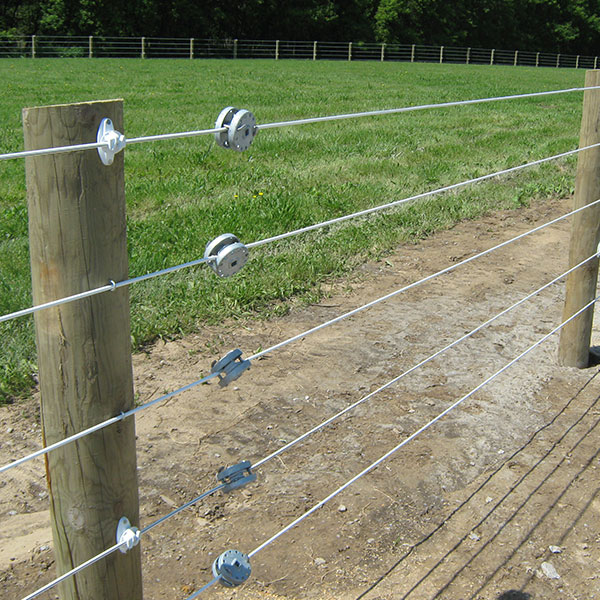

3. Posts and Stakes: The Skeleton

Step-in Posts: The most common type. A steel spike with a plastic or fiberglass body and built-in clips or reels. Look for models with a “step” that is comfortable to push with your boot. A mix of 3-4 foot “line posts” and a few taller “corner posts” is ideal.

Fiberglass Rods: Simple, cheap, and effective. They require separate plastic insulators but are incredibly lightweight for large-scale moves.

Reel Posts: These combine a step-in post with a built-in reel for the polywire. They are a game-changer for efficiency, allowing you to wind and unwind the fence without ever touching the ground.

4. Accessories: The Unsung Heroes

Gate Handle: An insulated handle that allows you to quickly disconnect and reconnect your fence to create a gate.

Testers/Voltmeters: Never guess your fence’s performance. A quality tester is non-negotiable. It tells you if you have a problem and helps you locate it.

Ground Rods: The most common cause of a weak fence is an inadequate ground system. You need at least 3 feet of grounding rod per joule of output from your energizer. Use multiple 6-foot galvanized steel rods, driven fully into the ground and connected with clamps.

Pigtails & Connectors: For splicing wires and making reliable connections.

The Art and Science of Setup and Grazing

Step 1: Layout and Planning

Before you set a single post, walk the area. Look for hazards like old wire, holes, or poisonous plants. Plan your paddock shape. A square is more area-efficient than a long, thin rectangle, which has more perimeter to fence for the same grass.

Step 2: The “Hot” Ground System

Set up your energizer correctly. If it’s a plug-in, follow the manual. For solar/battery units:

Connect the ground terminal to your ground rods. This is the most important connection.

Connect the “fence” or “hot” terminal to your fence wire.

Ensure the energizer itself is protected from the elements and from curious livestock.

Step 3: Building the Fence

Place your corner and end posts first. Brace them by driving them in at a slight angle or using a double post.

Unreel your conductor and attach it to the posts. It doesn’t need to be banjo-string tight; a little sag is fine and prevents breakage.

For cattle, one strand at nose height (30-36 inches) is often sufficient. For sheep and goats, two strands are better (12" and 30"). For pigs, a single low strand (8-12 inches) is often effective as they root under, not jump over.

Step 4: Introducing Livestock and Training

Never assume an animal knows a wire is electric.

Train in a small, permanent-fence enclosure: Set up a short section of hot portable fence inside a secure pen. Place a bucket of attractive feed on the other side. The animal will investigate, get a safe but memorable shock, and learn to respect the fence without the risk of escaping for miles.

Make sure the fence is “snappy” from day one. A weak, buzzing fence teaches animals they can push through it.

Implementing the Grazing Plan:

The goal is to move animals before they graze the forage below a certain height (e.g., 3-4 inches for cattle, 2-3 for sheep). This is the key to plant recovery.

- Calculate Your Allocation: Estimate the forage mass in your paddock and the daily intake of your herd. This will tell you how many days the paddock will last. Start with a 1-3 day rotation and adjust based on grass growth.

- The “One-Bite” System: In an ideal rotation, an animal should never graze the same plant twice in one cycle. They are moved to a fresh strip or paddock, leaving the previous one to recover fully.

Troubleshooting the Top Five Problems

Weak or No Shock: 95% of problems are here.

Check the Ground: This is culprit #1. Add more ground rods. Ensure the soil around them is moist.

Check the Voltmeter: Use it at the energizer, then 100 yards out. A significant voltage drop indicates a fault (leaning weed) or a broken conductor.

Find the Fault: Walk the line, looking for where grass, weeds, or a fallen branch are touching the wire. A fault finder tool is invaluable for long fences.

Animals Not Respecting the Fence:

Insufficient Power: They are learning they can push through. Crank up the joules.

Poor Training: Go back to the training pen.

Psychological Barriers: Add more visible polytape flags or use a second, lower strand to create a more imposing visual barrier.

Breaking Wires:

Too Tight: The fence should have some give. Animals running into a taut wire will break it; a loose wire will just bow.

Poor Quality Reels: Cheap reels can kink and weaken polywire over time. Invest in good ones.

Vegetation Shorting Out the Fence:

Mow or Graze a Line: Before setting up a fence in a weedy area, have sheep or goats graze the fence line, or mow it first.

Use a Higher-Impulse Energizer: A more powerful energizer can “blast” through light vegetation.

Wildlife Damage:

Deer and other wildlife can run through and break fences. While frustrating, it’s part of the system. Keep your repair kit (a few spare posts, a reel of wire, and some knots/connectors) with you at all times.

Conclusion: A Return to Managed Grasslands

Portable electric fencing is more than a convenience; it’s a paradigm shift. It returns control to the grazier, allowing you to dictate exactly where and when your animals eat. This simple act of moving a fence daily is a profound exercise in ecological stewardship. You are no longer just a livestock owner; you are a grass farmer, a soil builder, and a ecosystem manager.

The initial investment in a quality energizer, reels, and posts pays for itself not just in saved feed and fencing costs, but in the vibrant health of your land. It requires diligence, observation, and a willingness to learn, but the rewards—lush pastures, healthy animals, and a more resilient and profitable operation—are well worth the effort. Stop thinking of it as a temporary barrier, and start wielding it as your most powerful tool for a sustainable future.

English

English  中文简体

中文简体